Galactic Chemical Evolution

From the Big Bang to today

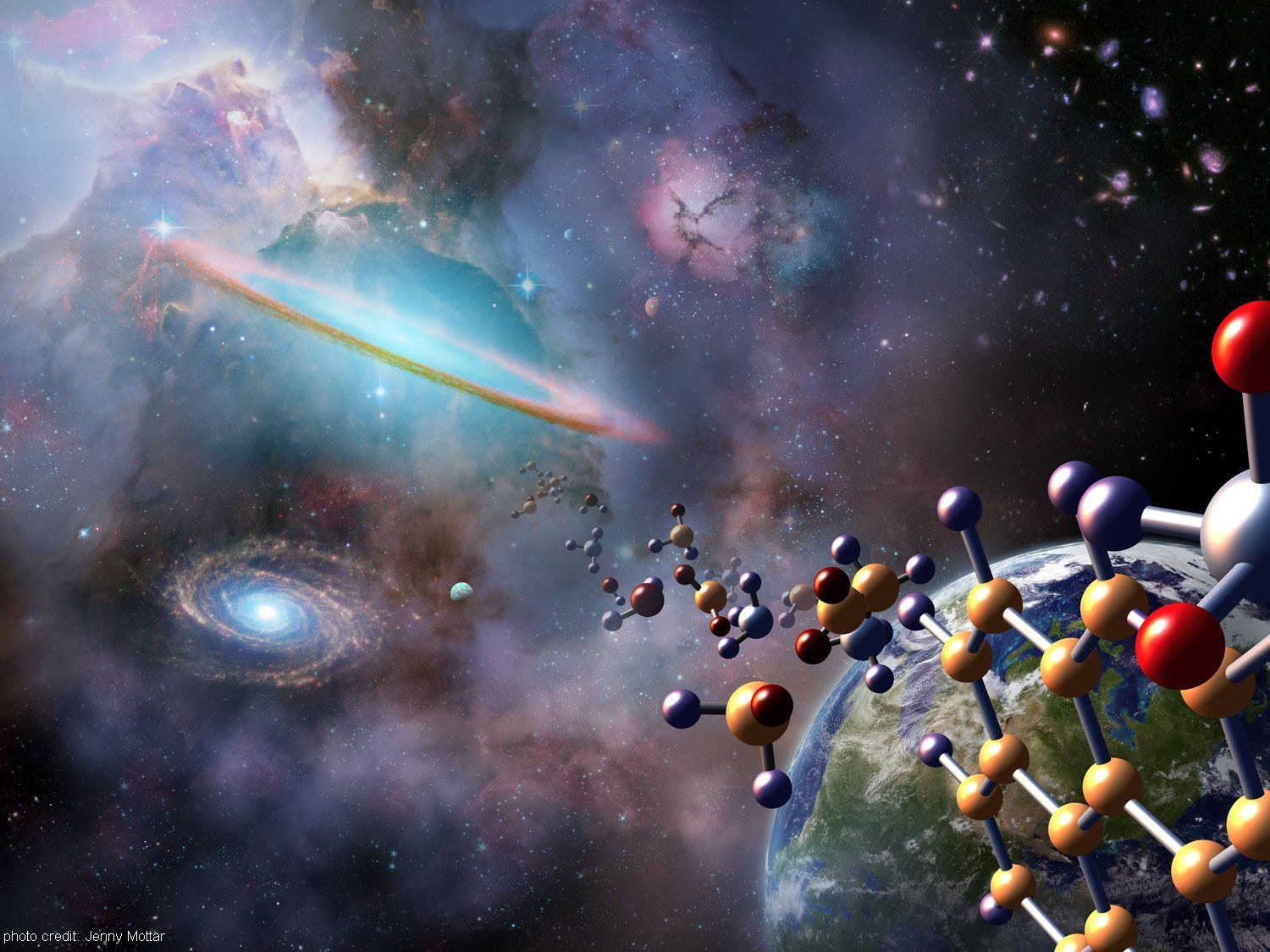

Galactic chemical evolution (GCE) is the field that studies how elements evolved in the universe. The big bang only produced hydrogen, helium, and a little bit of lithium. Aside from beryllium and boron, all other elements formed in stars in a process called nucleosynthesis. Depending on their initial masses stars undergo very different developments. A massive star can explode as a supernova at the end of its life while a low-mass star does not have enough energy stored up in order to explode so violently. Different elements and isotopes are associated with the production in different stellar environments. Galactic chemical evolution describes how this evolution of the elements took place since the beginning of the universe and is thus often described as galactic archeology. Below artistic impression (by Jenny Mottar, NASA) beautifully summarizes GCE in one image: from the big bang to complex molecules and the earth everything originates as stardust.

Metallicity

The periodic chart of the elements as chemists use it can be hard to remember, however, it is fairly easy for astronomers. In the astronomical sense, the universe consists of hydrogen, helium, and metals (yes, in the astronomical sense you breathe metals). The amount of metals in a star with respect to hydrogen is called the metallicity. Mass fractions of hydrogen to helium to metals are usually written in astronomy with the letters X, Y, and Z, respectively. The mass fractions of hydrogen, helium, and metals in the sun for example are: Xsun = 0.7381, Ysun = 0.2485, and Zsun = 0.0134. Knowing this number for the sun, any star’s metallicity can be expressed in terms of the solar metallicty. Metallicity can however also be expressed as a chemical abundance ratio. Here, the abundance of iron is often measured in a star and used as a proxy for the total metallicity. This abundance ratio is typically written as:

$$ [\rm{Fe}/\rm{H}] = \log_{10} \left( \frac{N_{\rm{Fe}}}{N_{\rm{H}}} \right)_{\rm{star}} - \log_{10} \left( \frac{N_{\rm{Fe}}}{N _{\rm{H}}} \right)_{\rm{sun}}$$

Since the big bang did not produce metals a first order GCE model can assume that the metallicity of an object is correlated to its age, i.e., an older object started out with a lower metallicty. This is assumption is correct up to a certain degree, however, breaks down when looking at the details of GCE.

Observables

Astronomical observations

Traditionally GCE is studied in detail by astronomical observations, specifically spectroscopy. This allows the determination of the elemental composition of stars and, in for certain elements, their isotopic composition. A variety of different stars can be observed, which allows us to study the distribution of elements within the galaxy. Furthermore, different stars have different ages. The elemental starting comopsition of a given star will be observable throughout most of its life, thus astronomical observations also allow us to look at GCE in time.

Stardust grain measurements

Stardust grains also allow us to study GCE. While the elemental composition of these grains is primarily dominated by the chemistry of the condensing stellar outflow and is thus not representative of the parent star’s composition, stardust grains are excellent tracers for the isotopic comopsition of stars.

Silicon isotopes in mainstream grains and the puzzling conclusion

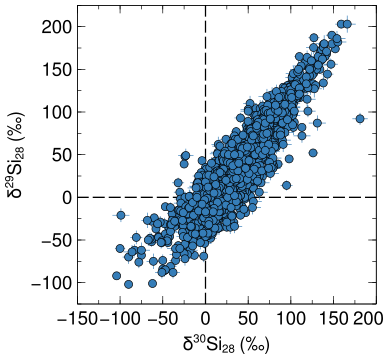

The figure below shows the silicon isotopic composition of all mainstream SiC stardust grains from low-mass stars taken from the presolar grain database. Plotted are all measurement that have isotope ratio measurements with lower than 10‰ uncertainties.

The axes labels are in delta units and describe the deviation of the sample from a standard (here the solar average) in per thousands:

$$ \delta ^{i}\rm{Si}_{28} = \left[\frac{\left(\frac{^{i}\rm{Si}}{^{28}\rm{Si}}\right) _{\rm{sample}}}{\left(\frac{^{i}\rm{Si}}{^{28}\rm{Si}}\right) _{\rm{standard}}} - 1\right] \times 1000 $$

The dashed line at the origin of the plot represents the solar isotopic composotion of silicon.

From GCE calculations we expect that 28Si forms early on and that the isotopes 29Si and 30Si form later on from 28Si. Silicon-28 is thus also called a primary isotope, while 29,30Si are secondary isotopes. We know however that presolar grains are older than the solar system, thus the material from which their stars formed came together before the solar system formed. A low-mass star, such as each parent star of a grain shown in the figure above, does not effectively produce 29Si and only produces a little bit (a few tens of ‰) of 30Si. Silicon isotopes are thus excellent proxies to study GCE.

What is going on then in the figure above? A lot of the grains are clearly enriched in 29Si and 30Si compared to the solar system. In the age-metallicity correlated GCE picture these grains thus seem younger than the solar system. The silicon isotopic composition of presolar grains thus clearly requires that GCE takes place more heterogeneously.

Other GCE proxies tell the same story

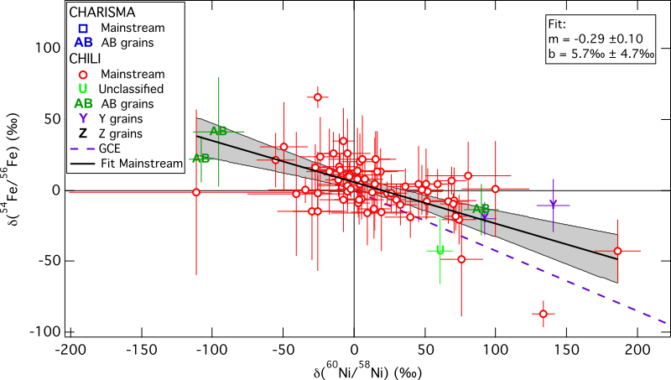

In a recent study we tested if the same holds true for the isotopic composition of iron and nickel. The best isotopes to use as GCE proxies here are 54Fe and 60Ni. The figure below shows our results:

The dashed, purple line shows the GCE model by Kobayashi et al. (2011) in comparison with our measurements. This linear GCE model ends at solar composition and for older objects shows a decrease in 54Fe and an enhancement in 60Ni. Many of the measured stardust grains look more evolved than the solar system itself, which agrees with the silicion isotopic measurements and also requries GCE to take place heterogeneously.

Measurements of stardust grains along with astronomical observations yield important constraints for our understanding of GCE. Astronomical observations are often limited to determine the elemental abundance. Stardust grains on the other hand do not allow us to determine their exact parent star, however, enable an excellent understanding of the isotopic evolution of GCE. The two techniques are thus highly complementary for studying GCE.